Overview:

- Water utilities in Houston and across Texas still don’t know whether thousands of their customers get drinking water through lead pipes.

- The EPA set an October 16 deadline for water systems to inventory their service lines, but Houston Landing found some did more investigating than others.

- This is the first time water systems nationwide have been required to tell customers what they know about lead pipes at individual addresses.

Nearly four years ago, utilities in Houston and across the country were directed by the Environmental Protection Agency to inventory their systems and identify which homes and other buildings get drinking water delivered through pipes made of or contaminated with lead.

But thousands of customers still will have no idea whether their water service lines contain toxic lead – even after Wednesday’s (Oct. 16) deadline for utilities to report their findings, according to information obtained by Houston Landing from a sampling of water utilities in the metro area and across the state.

In Houston, where the city’s water system dates back to 1879, officials still don’t know the type of pipe used in more than 80 percent of water service lines, a public works spokesperson told Houston Landing. About 429,000 of the system’s customers soon will receive letters alerting them that the lead status of their lines is unknown.

It’s going to be up to these customers – and likely thousands more across the country – to figure it out for themselves. At least for now.

The EPA estimates that about 9 million lead service lines nationwide connect utilities’ water mains to individual homes and buildings. These lines deliver drinking water that poses a potential health threat, especially to children and pregnant women, because they can release lead particles.

Lead exposure can damage a child’s developing brain and body, causing speech, hearing, learning and behavioral problems. Adults are at increased risk of heart disease, high blood pressure and kidney problems.

Lead service lines, which were the type responsible for contaminating water in Flint, Mich., were primarily installed in the U.S. during the late 1800s through the 1940s and are often located in older, lower-income neighborhoods and communities of color. The risky pipes utilities are supposed to identify not only those that are made of lead, but also galvanized pipes that may have absorbed lead from previously being downstream of a lead pipe.

It’s unclear how many lead service lines are in Texas. Some researchers have estimated, based on industry surveys and the age of housing, that Texas has far fewer lead service lines per capita than states in other parts of the country. The EPA estimates Texas has about 380,000 lead lines.

Exactly where are all these lines? Some water utilities in the Houston metro area have been far more aggressive than others in their efforts to look for them, Houston Landing found.

Galveston and Sugar Land proactive inspections

In Galveston, for example, officials said they have systematically excavated and tested nearly all of the city’s service lines as part of ongoing meter replacement programs and routine line maintenance and repairs.

The City of Sugar Land’s water system also has used physical line inspections during routine maintenance and their meter replacement program, along with intensive records reviews, to be able to determine the status of all their lines.

Other utilities appear to have relied primarily or entirely on searching through a wide range of old system records and other archival documents – the minimum required by the EPA – with varying levels of success.

This variation in efforts is playing out across the state, said Russell Hamilton, executive director of the Texas Water Utilities Association, whose members include operators from big city utilities, as well as small water systems that serve mobile home parks.

“Some folks are taking it really serious. Some folks are kind of giving it a cursory I’ll see what I can get done, kind of an attitude,” Hamilton said.

And some may not even turn in an inventory, he said. “I’m just curious as to how many people blew it off and didn’t do it,” Hamilton said, recounting a conversation at a recent association event with an operator whose water system serves about 1,200 people.

“I said: How’s your inventory coming? He said, ‘I’m not doing it.’ I said: How come? ‘Because I’m retiring in six months, and it’s not going to be my problem,’” said Hamilton, who did not identify the operator.

Lead pipe results to come but not perfect

A detailed accounting of what each of the thousands of water systems across Houston and the state knows — or doesn’t know — about individual water lines won’t start to become clear until after Wednesday. That’s when EPA rules require Texas water systems to submit their inventories to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and also make inventory information publicly available.

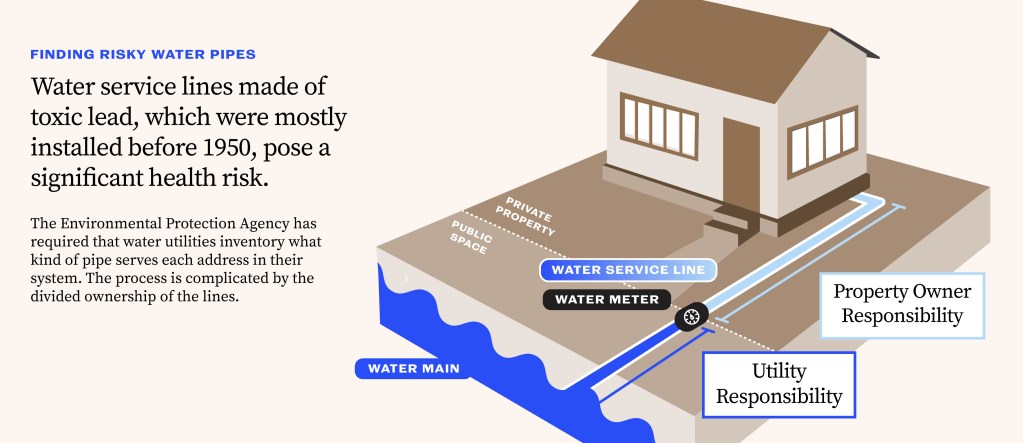

The inventory process is complicated by the passage of decades since lead lines were installed and incomplete water system records about old installations and line replacements. Another hurdle: the ownership of the water service line to each property is usually split between the utility and the property owner. Utilities generally own the segment of pipe connecting their water main to the water meter; the pipe from the water meter to the building generally belongs to the property owner.

Despite the divided ownership of water service lines, the EPA required water systems to include both segments of pipe – which may be made from different materials — in their inventories.

“Our sense is the utilities are making good progress,” said Greg Kail, director of communications for the American Water Works Association, whose member utilities supply about 80 percent of North America’s drinking water. “It is a starting point for many utilities and they’re going to be updating these over the course of years.”

Earlier this month, the EPA announced a final rule that will require most drinking water systems to dig up and replace lead service lines within 10 years. “Legacy lead pipes, which have delivered drinking water to homes for decades, have exposed generations of Americans to toxic lead and will continue to do so until they are removed,” the EPA said in a statement.

Before that can happen, the lead lines have to be located.

Most Texas water systems still had not turned in their inventories as of Oct. 8, according to figures TCEQ provided to the Houston Landing. Just 1,463 public water systems out of 5,603 had submitted their reports.

These early reporting systems collectively found just 1,212 lead service lines among more than 1.5 million pipes across their systems. They also found 12,202 risky galvanized pipes that require replacement.

The lead status remains unknown for more than 135,000 service lines in these systems, which appear to include many small water providers across the state. On average, these systems serve 3,300 people, the TCEQ said. The largest system among the early filers provides water to about 232,000 people.

Some of the Houston area’s large water systems told Houston landing they were still finishing their inventories but would have detailed data to share publicly by Wednesday’s deadline.

The City of Houston’s public works department, which operates what are technically six water systems that serve about 2.2 million people, told Houston Landing that its inventory has not found any lead service lines. But the city has so far only been able to determine the pipe materials for 86,210 service lines, said Erin Jones, acting communications director for Houston Public Works. That’s just 16 percent of the total.

The department doesn’t know what kind of pipe was used in the rest of the 447,955 service lines across the system, she said.

“Over 400,000 people are going to be getting these letters about unknown materials because we don’t know what’s on their side of the service line,” Jones said. Some customers have properties with multiple unknown lines, she said, but will only receive one letter in their water bill.

Materials are also unknown on the city-owned portions of about 200,000 service lines, Jones said.

The Houston Public Works over the weekend posted a searchable water service line inventory map on its website that displays the pipe status at individual properties. Where the pipes are unknown, there is a link to a survey where the city is asking customers to self-report what kind of service line they have, including uploading photos of their pipe.

Citing the city’s ongoing work compiling and analyzing data to meet Wednesday’s inventory deadline, Jones said staff were not available to answer questions that Houston Landing began asking last month about the process the city used to investigate the service lines throughout its system and why the status of so many lines remain unknown.

Jones noted that because the EPA historically hasn’t required the tracking of water line materials, it will take large systems time to assess their pipes. EPA inventory rules allow utilities to categorize lines as having an unknown lead status, recognizing that systems with limited or nonexistent records will have to rely on time-consuming physical inspections.

Houston Public Works in 2021 told the EPA there were an estimated 302,000 lead service lines in its system. But it was a mistake – they should have been reported as lines with unknown materials, Jones said. The department has worked with state and federal regulators to correct this past erroneous reporting.

“Currently there are no known service lines made with lead,” she said.

The department had nobody available to answer questions about what their EPA-mandated records review has revealed about the potential presence of lead service lines across the system or the past discovery and replacement of lead lines.

Houston Landing’s review of the city’s municipal codes and ordinances for a sampling of years from 1871 through 1958 indicate that “lead pipe” was an allowable material back then that the city expected to be present in its water system.

MORE ON LEAD PIPES

Want to know about lead in your drinking water? Now you can get the facts

by Alison Young

These records in 1942 and 1958 make a point of specifying that the part of the service connection extending from the water main to the curb, “including the corporation cock, lead pipe, galvanized pipe or cast-iron pipe, stopcock, and also the meter and meter box” are controlled and maintained by the water department. The 1922 revised city code makes reference to “lead pipe to curb” as part of the “service pipe from the main.”

The Houston Public Works did not respond to questions about whether these records indicate the historic use of lead pipes to deliver water to at least some city customers.

Jones said water department officials would be available to answer questions after the inventory is completed.

Galveston surprised by lead pipe count

In Galveston, which has a smaller water system that like Houston’s dates back to the late 1800s, the physical inspection of customers’ service lines has produced clear – yet unexpected — answers about the type of pipe at each property.

The Galveston city water system initially estimated it would find 3,500 to 5,000 lead service lines, based on an initial review of old permits and records. Water officials had even begun contemplating how to pay the $3,400 replacement cost for each.

With about 95 percent of Galveston’s service lines dug up and evaluated as of last week, however, the city has found just 27 lead service lines.

“It wasn’t anywhere as bad as we feared,” said Trino Pedraza, Galveston’s executive director of public works and utilities.

The lead piping is mostly on the customer’s side of the service line – meaning it will be their responsibility to get it replaced, Pedraza said. Just seven of the lead pipes identified so far involve the city-owned portion of the lines, he said.

Galveston identified an additional 961 galvanized lines requiring replacement, because they have the potential to have absorbed lead. Only two of those lines involve the portion owned by the city.

“The lead lines are really scattered throughout the island. There’s not really a cluster of them in any particular area. That was something that was surprising,” said Ava Cares, the city’s program and maintenance utilities supervisor.

Even more surprising: Two lead service lines were found on the west end of the island in an area of newer homes built after the use of lead in pipes and plumbing in Texas was banned in 1988. “We were kind of curious how that got in,” Pedraza said.

One theory is that perhaps the old lead service lines were installed years earlier in preparation for a development project that was abandoned, he said. Then, when the newer homes were constructed years later, the homes got connected to the service lines that were already buried in the ground.

Galveston will be posting a searchable map on its website this week and will notify customers that have lead and risky galvanized lines.

Galveston took advantage of an existing water meter replacement project to get detailed information about its lines. “We already had contractors on site going to every single meter and changing them out,” Cares said.

The work already required digging on both sides of the meter, so the city simply added a change order to the contract calling for a bit more digging on each side of the meter box, plus the testing of any metallic pipe. “We just happen to be fortunate to be embarking on this journey with this meter change out program,” Pedraza said.

Pipe transparency may drive change

Wednesday’s inventory deadline is important because it is the first time that water systems nationwide will be required to make public an initial accounting of what their service pipes are made of, said Tom Neltner, national director for Unleaded Kids, a nonprofit group that focuses on gaps in lead policy issues.

This transparency has the potential to mobilize the public to demand fixes for this hidden public health problem, he said.

The EPA is requiring water systems to publicly disclose certain inventory information, including the location of each line that was classified as a lead or risky galvanized pipe requiring replacement. The EPA recommends that systems also publicly share information about the status of all their other service lines, regardless of their materials, but this is not required.

Utilities that serve more than 50,000 people must post their inventory information online, EPA rules show. Smaller systems aren’t required to post online as long as they make the information available some other way, such as by mail or at the system’s office.

In addition, within 30 days of turning in their inventory, the EPA is requiring that utilities notify individual customers who have lead service lines, galvanized lines requiring replacement, or who have pipes with an unknown lead status.

Neltner said that once the public starts being able to look up the status of water lines at individual addresses, there will be public pressure to identify unknown pipes and replace those that are made of lead.

Neltner said: “People are going to start checking their property, or prospective buyers or prospective renters are going to be checking their property and asking: Do I really want to drink water through a lead pipe or a lead straw?”