For nearly two decades, Texas schools have gone easier on kids.

Aiming to keep more students in class and under adult supervision, state legislators and many school districts limited in-school and out-of-school suspensions. At the same time, education leaders increasingly substituted tough discipline for restorative discipline practices designed to help troublemakers understand and correct their behavior.

But in the wake of the pandemic, students increasingly acted out in school — with sometimes dangerous results for classmates and teachers. Educators across Texas have recalled stories of broken noses, shattered glass and flying desks, with children as young as 4 years old responsible.

Now, some Houston-area school districts and Republican state legislators are rallying around a bill that would give educators more power to discipline students, reversing the more progressive approach that kept more children in the classroom and on campus.

The proposal could have far-reaching effects on Texas’ youngest and most vulnerable students, who could get kicked out of class, suspended and expelled more often. In the Houston area, many of the districts serving the largest number of students of color and children from lower-income families — including Aldine, Alief and Spring ISDs — already rely more heavily on discipline.

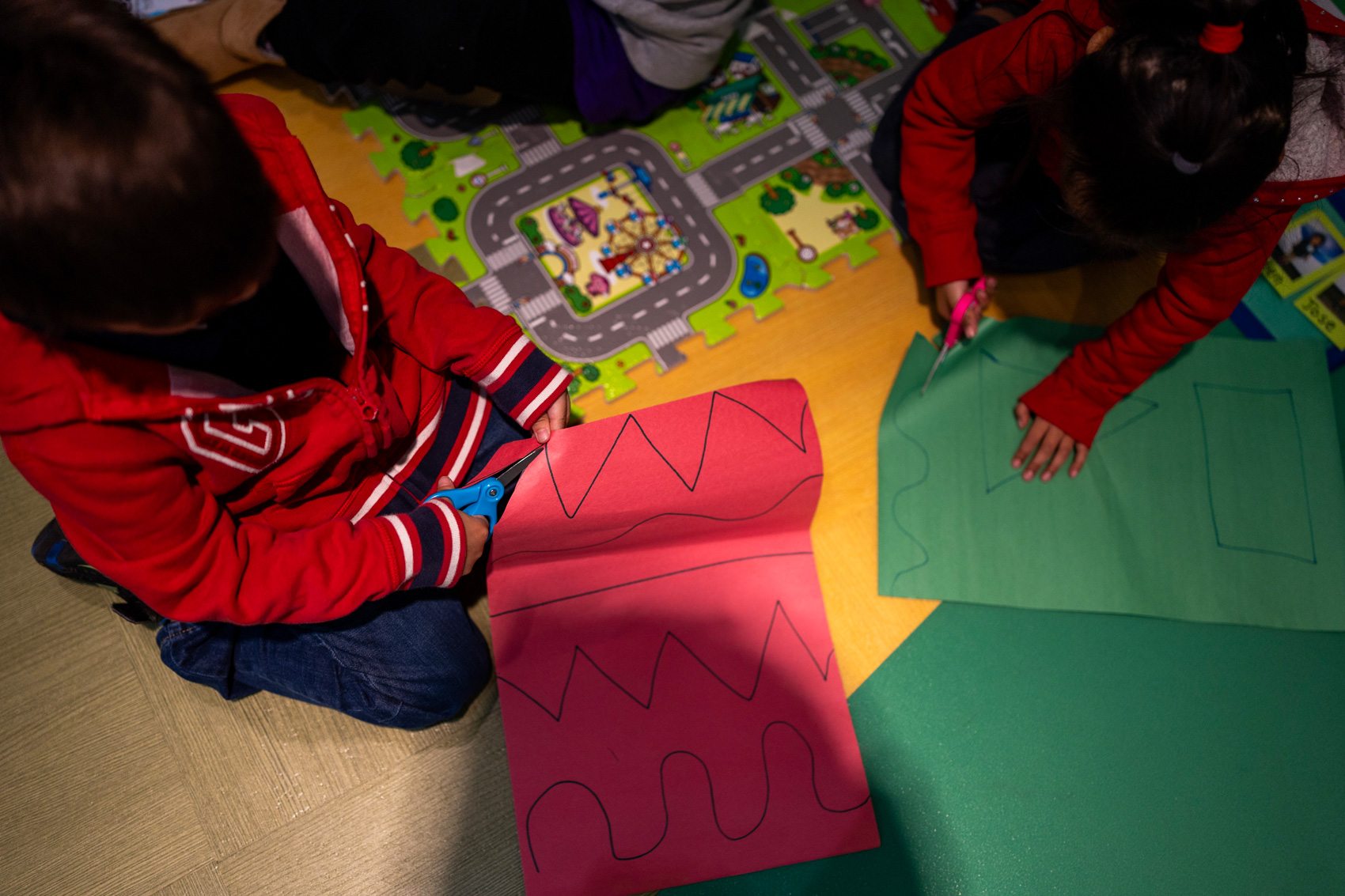

Under the proposal, Texas school districts could once again issue out-of-school suspensions to homeless students and children in grades prekindergarten through 2 for causing “significant classroom disruption,” undoing protections put in place in the late 2010s. School leaders also could resume sending kids to in-school suspension for more than three days, expel repeat offenders more easily and discipline students for serious offenses that take place outside of school.

For supporters of House Bill 6, which is co-sponsored by most House Republicans, the legislation is a needed correction that would give educators more tools in their arsenal to keep classrooms safe for well-behaved students and overwhelmed staff. A recent state-led survey found discipline and a safe work environment was the second-most cited issue among teachers who recently left the field.

“At the end of the day, this bill is about standing with our educators, ensuring that teachers in our classrooms have the support that they need and that they deserve to create a structured and focused learning environment,” said state Rep. Jeff Leach, R-Plano, the primary author of the bill.

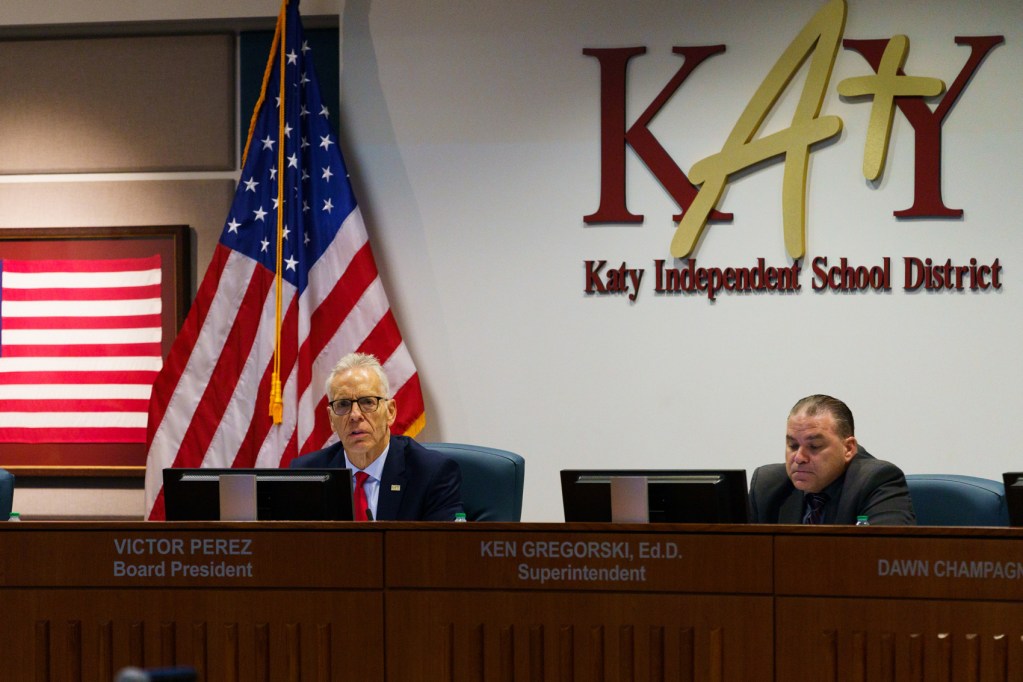

About 40 Texas school districts, including Cy-Fair and Katy ISDs, have thrown their support behind the bill.

But critics of the bill, including leading Democrats in the House, argue that suspensions and other forms of discipline that take kids out of classrooms can backfire on students, removing much-needed support and making school a less-welcoming place. In recent years, several Houston-area districts have scaled back on stricter punishments, arguing it jeopardizes their long-term academic success.

“Alief ISD’s approach to student discipline is that they cannot learn if they are at home,” an Alief spokesperson said in a statement.

Back to the drawing board?

State education leaders and Texas lawmakers were generally united for more than a decade in pushing to curtail harsher disciplinary practices.

Between 2007-08 and 2018-19, the last full year before the pandemic, Texas public schools nearly cut in half their in-school and out-of-school suspension rates. Districts also sent kids to disciplinary alternative education programs 35 percent less during that time.

Meanwhile, a 2017 law passed with bipartisan support prohibited Texas school districts from suspending students below the third grade, except in response to offenses involving violence, weapons, drugs or alcohol. Lawmakers enacted the same protections for homeless students in 2019.

But students’ mental health worsened during and after the pandemic. A 2022 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found 37 percent of students surveyed nationwide experienced poor mental health during the pandemic. In the first six months of 2021, children’s hospitals reported a 14 percent jump in mental health-related visits among children aged 5 to 17 compared to the same time period in 2019.

Spring Superintendent Lupita Hinojosa said the pandemic’s impact on students didn’t end with the return to in-person school. Then, natural disasters like Winter Storm Uri and the spring 2024 derecho further destabilized families, she said.

“These community stressors also will come into the schools,” Hinojosa said in an interview earlier this month. “Having a place for children to come and be safe and have their meals and have relationships, lasting relationships, with teachers, this is what holds a community together.”

In Region 4, a state-designated area that covers school districts in Harris, Fort Bend, Galveston and Brazoria counties, total disciplinary infractions are still slightly down from pre-pandemic levels.

However, Region 4 schools have seen a surge in violent offenses. The number of assaults resulting in discipline roughly doubled from 1,300 in 2018-19 to 2,750 in the last school year. Disciplinary actions for fighting also increased slightly during the same time frame, rising from 11,700 to 13,500 infractions.

In light of behavior trends, the 40 school districts supporting House Bill 6 formed the Student Behavior Management Coalition, bringing together a mix of education leaders from larger conservative-leaning districts, rural areas and communities already disciplining students at high rates. The coalition asked legislators for many of the flexibilities included in the House bill, plus more money for student mental health services and classroom management training.

Several members of the coalition lobbied for the bill last week during a House Public Education hearing, relaying tales of school leaders hamstrung by state law.

Cy-Fair ISD Superintendent Douglas Killian recounted how a student in the district fatally shot a classmate in the head off-campus, filmed the shooting and put the video on social media earlier this month. Killian said the district couldn’t discipline the student because the shooting happened off-campus. Police didn’t arrest the 15-year-old student on a murder charge for a week.

“That student was back at our school, in our alternative program, where they were going to school the next day,” Killian said.

Sticking with their plans

If the House bill passes, history suggests Texas’ Black, Latino and lower-income children, along with students with disabilities, would be impacted the most.

However, disciplinary approaches would still vary widely by district, giving supporters of a more tolerant approach the opportunity to build on their reforms.

Spring administrators, for example, said in a statement that they had no plans to reverse course on their efforts to reduce harsh discipline and find alternative punishments for at-risk students. The district registered an out-of-school suspension rate roughly three times higher than the state average in 2023-24.

Spring leaders are implementing a social-emotional learning curriculum to address behavior issues, regularly reviewing the district’s code of conduct and instituting a second chance program for students caught with e-cigarettes. Still, district leaders acknowledged suspension rates could increase once more if the bill passes.

”If House Bill 6 were to remove certain guardrails around student suspensions, it could impact these efforts by potentially increasing exclusionary discipline rates,” officials said. “While we recognize the need for appropriate disciplinary measures, we also believe in the value of interventions that address behavioral issues while keeping students engaged in their education.”

In Alief, which has seen a 16 percent drop in out-of-school suspensions since 2018-19, district leaders said they have no plans to lobby in favor of the House bill.

“We have embedded behavior support and interventions to keep students in school and support them while they are here,” an Alief spokesperson said in a statement.

Administrators in Aldine ISD, which had the region’s second-highest suspension rate among large districts, said they will continue to “invest in relationships, consistent uniform classroom management techniques, and revisions in how we address consequences.” The district is not a member of the Student Behavior Management Coalition.

Houston ISD Deputy Chief of Schools Daniel Girard said the district had not been approached by the Student Behavior Management Coalition, but would continue to discipline students “in compliance with the law.” HISD’s suspension rate is slightly higher than state average but lower than many large districts in Greater Houston.

“HISD believes the best tool we have is high-quality instruction,” Girard said in a statement. “This involves supporting educators so that they can keep students learning and engaged with their coursework.”

Walking the line

The House bill is flush with Republican support in the lower chamber, but its prospects in the Senate remain unclear.

Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick, who presides over the Senate, did not include the proposal in his list of 40 priority bills for the legislative session. A bill with identical language to the House bill filed by state Sen. Mayes Middleton, R-Galveston, sits with no co-sponsors.

While legislators and district officials alike agree that student misconduct is a serious problem, not everyone agrees on how to deal with it.

In last week’s legislative committee hearing, state Rep. Alma Allen, D-Houston, worried that the bill would worsen the school-to-prison pipeline for at-risk students, branding children as troublemakers early on while failing to address the root causes of misbehavior.

“I don’t see anything positive in this bill,” Allen said. “Everything is a negative for children.”

State Rep. James Talarico, D-Austin, voiced concerns that increasing out-of-school suspensions could push students deeper into dangerous or unstable home situations. He argued that students often misbehave in classrooms that lack the ground rules and structure they need to succeed.

“Classroom management is a lost art,” Talarico said. “These programs focus so much on academics … but if we’re not focusing on classroom management, the rest of it doesn’t matter.”

Killian, the Cy-Fair superintendent, agreed that good classroom management can prevent 99 percent of bad behavior.

“We’re asking for this tool in our tool chest to be able to address that 1 percent that need that extra help,” Killian said.

Toni Lopez, the deputy superintendent of staff and academic achievement at Pasadena ISD, said the district aspires to limit its reliance on tough discipline. Still, Lopez said Pasadena school leaders have to keep students and staff safe — and mandatory rules about discipline can tie their hands.

“If we could go a whole school year and not one kid be suspended, that would be huge, and it would make my heart super happy,” said Lopez, who was named Pasadena’s lone finalist for superintendent earlier this month. “But I also don’t want a kid sitting in a classroom with 25 other kids and being dangerous to other kids. That balance is delicate. It’s very, very delicate.”

Staff writers Asher Lehrer-Small and Angelica Perez contributed to this report.