The mistake happened in an instant.

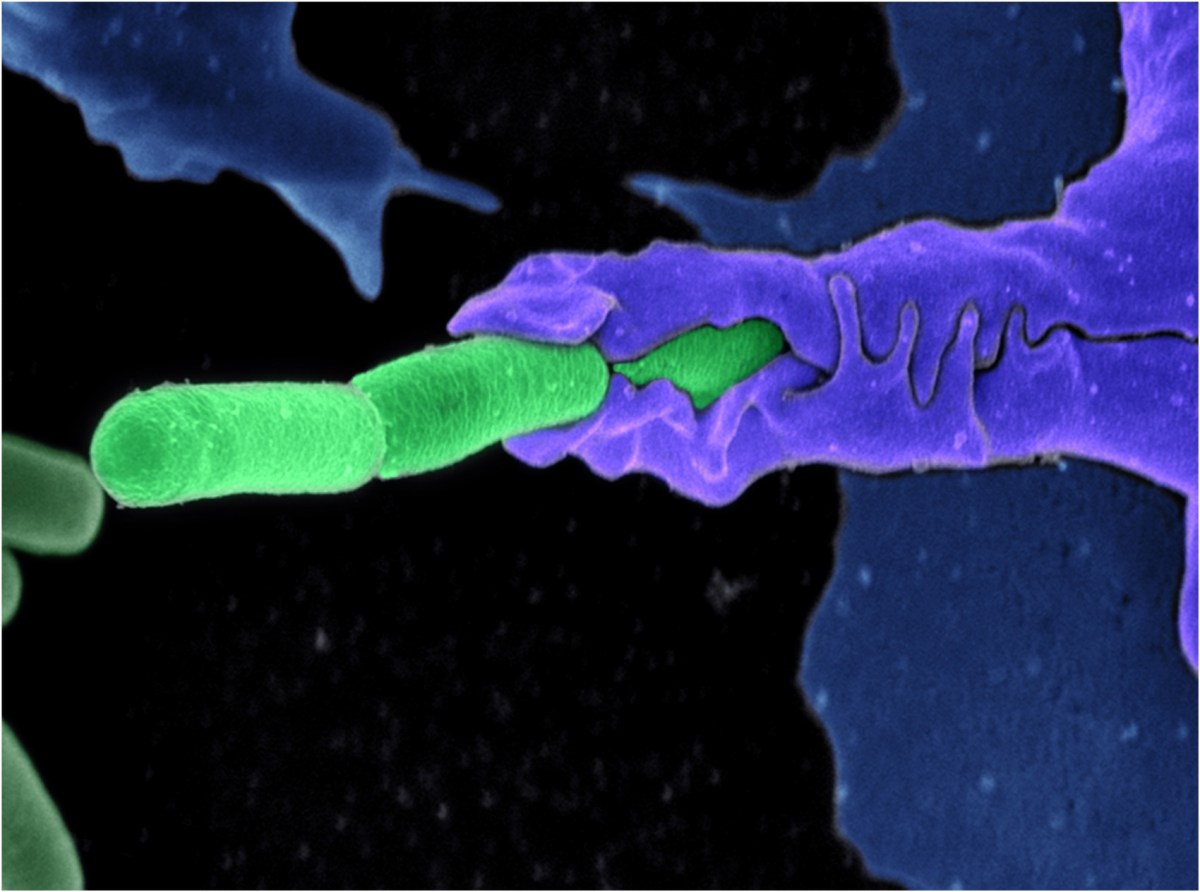

Inside one of the biosafety level 4 labs at the Galveston National Laboratory – where scientists wear full-body moonsuit-like gear as they study some of the world’s most dangerous microbes – a lab worker was uncapping a needle.

The worker had just been handling a guinea pig that was infected with Chapare virus, which has caused deadly outbreaks of a hemorrhagic fever disease in Bolivia and for which there is no treatment other than fluids and supportive care.

As the lab worker uncapped the new needle, it accidentally plunged through their layered gloves and into their finger.

The mishap last August is one of three incidents last year where workers were potentially exposed to infectious pathogens inside research labs at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, according to an annual biosafety incident summary lab officials released this week.

UTMB officials said none of the lab workers were infected in the 2024 safety breaches, which also involved an incident in October in with anthrax bacteria, which can cause serious disease but is not contagious, and in December with Mayaro virus, which is spread by mosquitos and tends to cause a mild disease that includes fever, aches and a rash.

Although lab officials classified each incident as a potential exposure to the workers, they said the risks in each case were very low because of the many layers of precautions used in the labs.

“Because of the practices we have, we’ve never had a person become ill working in a lab,” Gene Olinger, director of the Galveston National Laboratory, told Houston Landing.

The Galveston National Lab and the UTMB-Galveston campus’ Robert E. Shope, MD, Laboratory are among only about 15 lab facilities in North America that have labs operating at biosafety level 4 (BSL-4), the highest level of containment used for studying the most dangerous pathogens.

For many years, UTMB has posted a list with synopsis information about incidents involving potential worker exposures at these two BSL-4 lab facilities and also the campus’ lower level research labs that study less dangerous pathogens. UTMB officials updated the list late Tuesday, adding the three 2024 incidents to their previous disclosure of 66 other incidents dating back to 2002.

The list does not include research lab incidents where UTMB officials determined there was no potential exposure. Over the years, the disclosed potential exposures have included needlesticks, cuts, animal bites, spilled specimens and a wide range of pathogens including Marburg virus, Nipah virus, Dengue virus, Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, West Nile virus and SARS-CoV-2. But none have resulted in any worker becoming infected, lab officials emphasized.

“I always talk about trust and transparency,” Olinger said. “Trust is we tell you that we have measures in place to protect the community. Transparency is saying this is what’s happening and sharing it.”

Each of the three incidents disclosed for 2024 had a low likelihood for the worker becoming infected, lab officials told the Landing. But each was treated as a potential exposure out of “an abundance of caution,” they said.

During the Chapare virus experiment where the needlestick incident occurred on Aug. 13, the lab worker had disinfected their gloved hands after handling the infected guinea pig. But not enough time had passed to ensure the chemical had fully inactivated any virus on the surface of the worker’s gloves, officials said. This created the potential for virus to be carried by the unused needle when it passed through the glove and into the person’s finger.

“The likelihood of any true exposure that could result in infection was profoundly low,” said Dr. Susan McLellan, a physician and the labs’ biosafety director for research-related infectious pathogens, who was consulted on the worker’s case.

In nature Chapare virus – which can cause a range of symptoms including bleeding – appears to primarily spread through close contact with infected rodents, although some healthcare workers appear to have become infected while treating infected patients.

With no post-exposure treatment available for Chapare virus, and the risk of infection deemed highly unlikely, the worker was instructed to monitor themselves in case any symptoms developed, the lab officials said.

The anthrax bacteria incident on Oct. 11 involved a worker in a biosafety level 3 lab sticking themselves with a needle while attempting to draw blood from an infected rabbit. “So this was again, an unused clean needle that was going to be used to draw a sample from an infected animal,” said Corrie Ntiforo, biosafety director for the labs.

McLellan said that while the risk of infection was “extremely tiny,” the worker opted to take a course of post-exposure antibiotics to protect against that risk.

The third 2024 exposure incident, on Dec. 19, involved a leaking specimen of Mayaro virus, which is found in parts of South America, Central America and the Caribbean and causes flu-like symptoms.

A virus specimen was being processed with a piece of lab equipment, called a homogenizer, that has the potential to create aerosolized particles. Because Mayaro virus doesn’t cause severe or deadly disease and in nature it is typically spread by mosquitos, it was being worked with in a biosafety level 2 lab, where workers generally wear gloves and a lab coat, but not any respiratory protection.

“One of the vials in the cassette either cracked or something happened, and a teeny, tiny bit of liquid came out of that, which in our world is a spill,” Ntiforo said.

Even though Mayaro virus isn’t spread through aerosol transmission in nature, the lab officials said the incident was classified as a potential exposure because of the possibility it might happen in a lab setting. There is no post-exposure treatment for Mayaro virus, it doesn’t cause severe illness and also doesn’t spread from person to person, they said.

Each of the safety incidents, which occurred during research aimed at developing disease treatments, was reviewed to find ways to prevent similar mishaps in the future, Ntiforo said. The needlestick incidents resulted in sharing guidance across the Galveston campus on best practices for safely uncapping needles, she said.

It is unusual for research labs to proactively release information about lab incidents. At most labs, incidents only become public as a result of journalists or others filing public records requests.

“I’ve always admired UTMB for doing this,” said David Gillum, a past-president of the biosafety association ABSA International and a Reno, Nev.-based biosafety consultant. “Other people should learn from it.”

At a time when public concern about lab safety has risen amid the possibility that the Covid-19 pandemic might have come from a lab accident in China, Gillum said transparency is an important way for scientific labs and the biotechnology industry to build public trust.

“If we holistically want to help the public be less fearful, we have to build the trust. And building the trust means you have to have difficult conversations,” Gillum said. “I give them props for doing it, because anytime you put out incidents like this you’re going to get potential scrutiny. A lot of places are not this transparent.”

Read the UTMB Galveston’s summary information about potential pathogen exposures in their research labs at this link.