My mom had barely entered the recovery room at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center when I began bombarding her with questions.

The nurses wouldn’t tell me, I told her. I needed to know if it was real.

“They found it, baby,” she said, smoothing my hair. “Dr. Leon told us it was no wonder you were in so much pain.”

I sobbed.

The pain was never in my head. It was never normal.

And now, after years of dismissive doctors and searching for answers, it had a name — endometriosis.

With my diagnosis, I became a part of a club I didn’t ask to join — the nearly 10 percent of women, transgender and gender-diverse people who have the disease.

Endometriosis is a chronic, inflammatory disease that occurs when tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows elsewhere in the body. It often causes debilitating pain, excruciating menstrual cycles, pain with sex, problems or pain with bowel movements, urination and infertility. There is no definitive cure or known cause.

I popped ibuprofen like candy during my periods to alleviate cramps that left me in the fetal position feeling like I was being cut in half with barbed wire. I was never far from a heating pad. I quietly planned my social life around my cycle. I told myself it was never that bad. Besides, periods were supposed to be like this, right?

For a disease that impacts 6.5 million women in the United States, the National Institutes of Health allocated $16 million — 0.038 percent of its $41.7 billion-plus health budget — to endometriosis research in 2022, according to a study published in Frontiers in Global Women’s Health. That works out to $2 per patient.

Diabetes and Crohn’s Disease have similar prevalences among U.S. women as endometriosis. NIH spent $31.30 per diabetes patient and $130.07 per Crohn’s patient.

It took over three years to get my diagnosis. I’m one of the lucky ones.

It takes most between four and 11 years, according to Yale Medicine.

Though predominantly found in the pelvic cavity, endometriosis has been found on nearly every organ in the body, including the kidney, lungs and brain.

related

Think you have endometriosis? Here is a resource guide for diagnosis, treatment and support

by McKenna Oxenden / Staff Writer

In my case, the endometriosis and scar tissue from a previous surgery was so extensive that it trapped some of my organs and put a stranglehold on my uterus. My right ovary was flat, glued to my pelvic sidewall. The right fallopian tube and ureter, which connects the kidneys to the bladder, also had to be freed. There were lesions other places, too.

An MRI also revealed that I have adenomyosis, in which the uterine lining grows into the muscle wall. It’s a condition closely related to endometriosis and many of the symptoms overlap. Even less is known and researched about adenomyosis compared to endometriosis and the only known cure is a hysterectomy.

‘Have you tried birth control?’

Looking back, I long had signs of endometriosis. My periods were irregular from the start and sometimes my body would swell, leaving me with a puffy, inflamed face and distended belly. Anemia has plagued me on and off. In college, I had bouts of back pain so bad I could barely walk at times. Each year my period cramps got worse, too.

I mentioned all of this to my doctors over the years. They told me my pain was normal, nothing to worry about, and offered birth control pills to help regulate my cycle. Because endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease, many birth control pills actually can make symptoms worse.

The disease wasn’t on my radar until my mid-20s.

I was 25 and regularly felt like I was being sliced with a razor blade from the inside out. My periods grew consistently heavier.

One day in the fall of 2021, I bled so heavily during my cycle that I wondered if I somehow was having a miscarriage.

Panicked, I called my OB-GYN.

She wasn’t concerned, but sent me for a “just-in-case” ultrasound, which revealed a grapefruit-sized cyst on my right ovary. My worsening periods and consistent back pain suddenly made sense and I was relieved — I would finally be pain free. I opted for surgical removal.

Less than six months later, my symptoms returned in full force.

Over the next three years, seven doctors in three different cities quashed my concerns:

“Phantom pain is a real thing.”

“You should get pregnant, it might help.”

“The only thing that is going to help you is birth control.”

One doctor misdiagnosed me with polycystic ovary syndrome, a hormonal condition. Her recommendation: Ozempic, the anti-diabetes drug currently enjoying widespread popularity as a weight loss shortcut. Another doctor, who claimed to be an endometriosis specialist, told me there was no way to know if I had the disease. He offered me birth control.

More than once, I fell down a rabbit hole playing Dr. Google with my symptoms, which seemed to match perfectly with endometriosis. If I actually had that disease, I told myself, a doctor surely would have been able to help.

My pain worsened. So did my rationalizations.

Sure, I was exhausted all the time, barely able to make it through a day without a nap, but it probably was just stress at work. Yeah, my lower back constantly ached, but I probably just overdid it horseback riding and working in the barn. When my period came, I knew I’d be chained to the couch with my heating pad. It could be worse though, right?

Hardly anyone knew the crippling pain I regularly experienced. It was invisible — and I was happy with that.

I reached my breaking point in early 2024.

The path to diagnosis

One of the most vital things when reporting a news story is finding the right sources. Often, that can take copious amounts of reading, going to community events and scouring social media to identify the right people.

I decided to approach endometriosis like a reporter.

Despite a patient pool in the millions, the lack of reliable information about the disease in the medical community is so dire that many people turn elsewhere for help. Nearly 215,000 people, for example, are in a Facebook group called Nancy’s Nook Endometriosis Education. The group has a lengthy list of resources to help jump-start users’ endometriosis knowledge with a list of doctors globally, questions to ask providers and surgical recovery tips.

There were more than 50,000 obstetrician gynecologists in the United States in 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. And yet, it’s estimated there are only between 200 and 300 specialists in the world who can properly treat and surgically remove endometriosis, according to Heather C. Guidone, the surgical program director at The Center for Endometriosis Care in Atlanta, which sees more than 1,500 endometriosis patients a year.

I’m working to forgive the doctors who waved me off, saying it was all normal. I now know they probably never were given the proper tools to correctly diagnose and treat women like me.

Guidone is sympathetic to the fact that medical schools have to teach students a high volume of information across numerous specialties, but said it shouldn’t come at the cost of sharing incorrect or outdated information about the disease, perpetuating the stereotype of endometriosis as just a period problem.

There is no formal accreditation to denote an endometriosis specialist, meaning there is nothing to stop doctors without the proper training from promoting themselves as specialists.

“We don’t allow folks who treat cancer or other diseases to call themselves specialists if they don’t meet certain benchmarks, but yet, in OB-GYN, anybody who treats endo can call themselves a specialist,” Guidone said.

True endometriosis specialists always will be gynecologists, but not every gynecologist is an endometriosis specialist, according to The Seckin Endometriosis Center. Specialists will have specific training in treating the disease and prioritize treating endometriosis patients rather than delivering babies or providing generalized women’s healthcare. Usually, these specialists, who often perform upwards of 200 surgeries a year, will have completed a fellowship in minimally invasive gynecologic surgery, with a focus on endometriosis, to learn to skillfully cut out the disease.

Endo surgery generally falls into two categories: ablation, which takes a laser to the diseased tissue and excision, which removes the tissue. The Endometriosis Foundation of Houston likens the two options to weeding a garden: ablation cuts the weed, excision takes the weed out by the root.

Excision is considered to be the gold standard among endometriosis specialists because it often leads to lower rates of recurrence.

Some doctors may suggest progesterone-only birth control or an IUD to help control symptoms, according to Pelvic Rehabilitation Medicine. In some cases, it can help alleviate or stop painful periods altogether — though it’s often considered a Bandaid solution among specialists because it does not eliminate endometriosis or shrink existing diseased tissue.

Patient-centered communities

The Endometriosis Foundation of Houston’s Facebook group, which has nearly 1,500 members, helped narrow my doctor search after reading dozens of first-hand accounts from local patients.

Alison Landolt co-founded the nonprofit in 2018, after meeting five other Houston women with endometriosis. The group turned their “pain into purpose” to make the endo landscape less lonely and easier to navigate.

“So many of us suffered through the misinformation that led to bad surgeries that made us sicker, and so we’re trying to help people not do that, shorten the time for diagnosis and lead people to effective treatment,” Landolt said.

EF Hou — purposefully pronounced “F you” — hosts webinars with endometriosis experts, meet-ups and has a scholarship for those looking to attend pelvic floor physical therapy, which is often essential for pain management. Many with endometriosis suffer from pelvic floor dysfunction, which can cause muscle spasms and difficulty in coordinating pelvic muscles to urinate or have a bowel movement. Physical therapy can help rehab those muscles.

Guidone, who works at the Center for Endometriosis Care, first was diagnosed with endometriosis more than 35 years ago. She started one of the first endo community support groups on AOL and has watched the landscape grow from simple support groups to well-armed information hubs. Even researchers are taking notice.

An analysis of about 35,000 posts and more than 350,000 comments in two different endometriosis communities on Reddit found a need for more high-quality information, and greater empathy from doctors.

In at least 49 percent of the posts, researchers found people seeking information about endometriosis; 29 percent involved people looking to hear about others’ experiences with the disease.

Endometriosis can feel incredibly isolating. Hopeless, even.

In these patient communities, I saw myself reflected in nearly every post, as people shared their symptoms and experiences navigating the medical system. I realized, in the best way possible, I wasn’t alone.

For the first time in years, I felt a glimmer of hope.

The communities helped me identify a few doctors — my sources so to speak — to begin the next reporting step: backgrounding. Just as I would with any story, I want to ensure my “source” is a good fit for me.

I read online reviews, verified credentials, looked at research they performed and made sure they had completed a fellowship in minimally invasive gynecological surgery, with a focus on endometriosis. I also looked to see if they received money from drug or medical device companies.

Ultimately, I scheduled an appointment with Dr. Mateo Leon, a minimally invasive gynecologic surgeon and assistant professor for the Department Of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences at UTHealth Houston.

Treatment, at last

When I first arrived at the Greater Heights office, there was no paperwork to fill out about my health history or symptoms. The staff told me Dr. Leon prefers to do it himself.

It was unlike any appointment I’d ever had. For more than half an hour, Dr. Leon and I talked. He asked thorough questions about what led me to the exam table in front of him. He listened.

Then, he apologized and said he was sorry on behalf of all of the doctors.

“The pain you’re experiencing,” Dr. Leon said, “is not normal.”

Having a uterus means you often are overlooked and ignored as your pain is minimized. Dr. Leon had not even physically examined me yet, but he had already validated my pain and my experience. I held back tears. I finally felt seen.

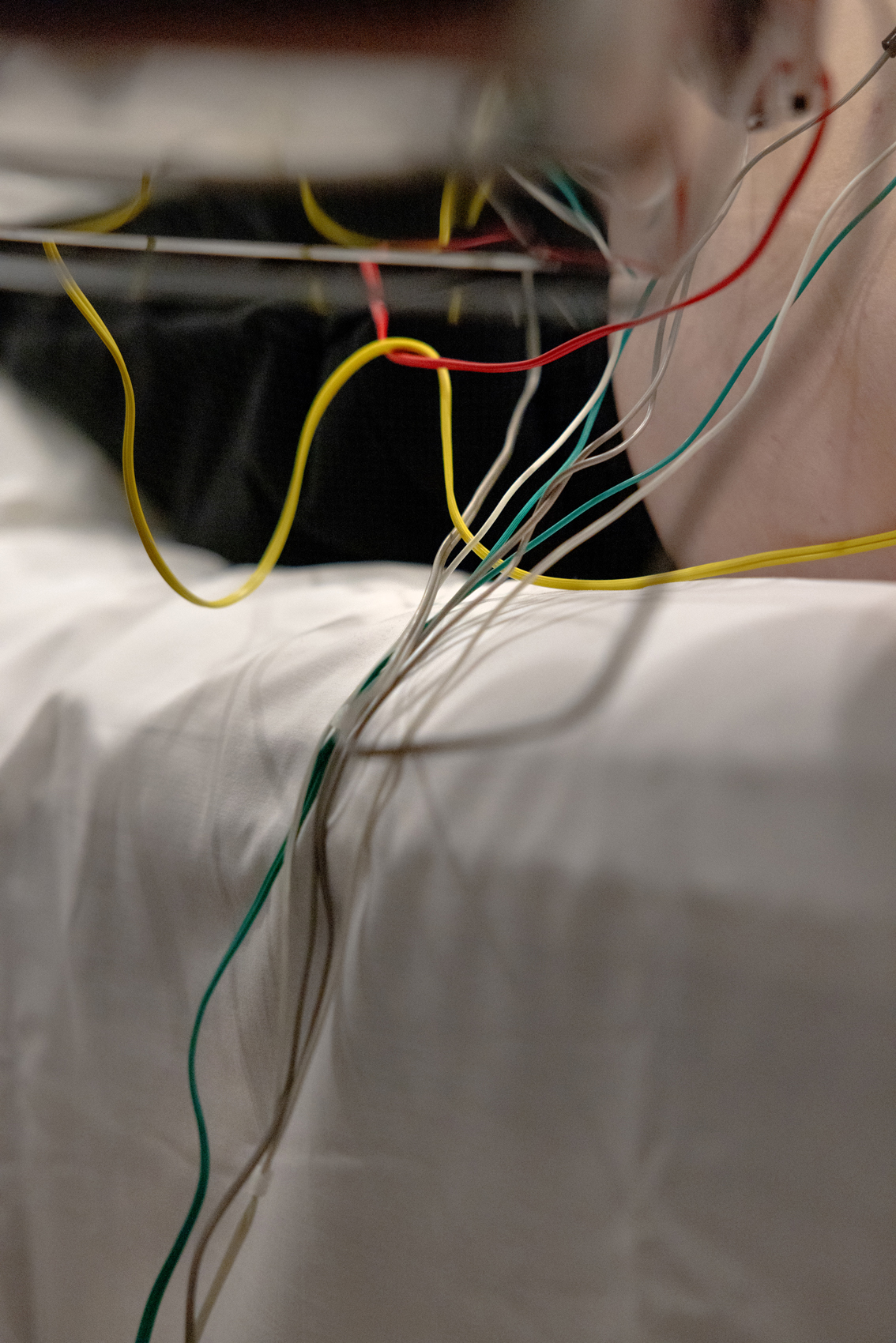

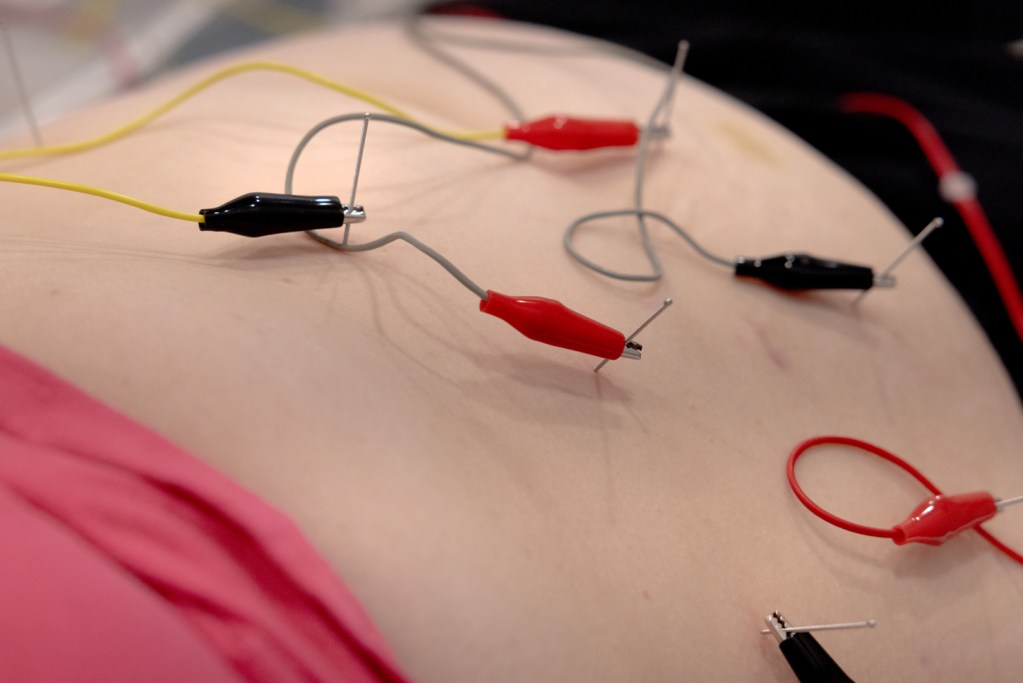

Five weeks later, I underwent excision surgery — the first step in a lifetime of managing this chronic disease.

Again, I am one of the lucky ones.

I was able to cut through the enormous barriers many face to receive proper treatment. There was no battle with my health insurance provider. My in-network specialist was just a short drive away. I could afford time off from work and the thousands of dollars necessary to meet my deductible.

The healing process has been lengthy and at times, tumultuous. Some days, I could almost forget I had an operation. Others, my boyfriend held me tight as I shrieked in pain. Occasionally, I felt worse than before surgery and wondered if it was a mistake.

“Recovery isn’t linear,” Dr. Leon told me more than once. “Sometimes it has to get worse before it gets better.”

It’s now been six months since I gained five new little scars on my belly. I couldn’t be happier with my progress.

I still have pain — but it’s slowly decreasing.

The flare-ups that left me incapacitated are less frequent. My joints and body aren’t as achy. I no longer experience heavy bleeding or crippling cramps during my cycle.

While excising the diseased tissue was essential, it was not a cure.

My muscles and nervous system have been in overdrive for years as the endometriosis ravaged my body. That impact can’t be reversed overnight and takes a multi-faceted approach to even begin to remedy.

At times, I feel like I have a second full-time job.

I go to pelvic floor physical therapy twice a week to help mobilize my scars and release pelvic muscles that have long been strained. Weekly acupuncture for pain management and to temper inflammation. Talk therapy once a week to process having a chronic illness.

There are other things, too, like eating more anti-inflammatory foods and drinking more water. I’m also working on moving my body, practicing mindfulness and learning to manage stress better.

I’m grateful I had the surgery. I’m grateful for my diagnosis. I’m grateful to have built a wonderful and compassionate healthcare team that empowers my decision making.

I’m also angry.

I’m angry I spent years being ignored by doctors. I’m angry at the money I wasted on painful tests that ultimately didn’t matter. I’m angry that managing this disease is so much work. I’m angry it’s so widely misunderstood. I’m angry it’s something I’m going to have to manage the rest of my life.

And I’m angry there is no way to truly know what this disease might continue to rob me of — whether I’ll need more surgeries or be able to have children.

Openly talking about your period is inherently uncomfortable. I feel I owe it, though, to those who have, are and will fight this fight.

My endometriosis story is still unfolding and it’s scary to think of all the unknowns. It’s a work in progress to make peace with it.

For now, I’m focusing on what I do know: A renewed faith that I am my own best advocate. The great support system I’ve built to shepherd me through the uncertainties. And the fact I’m never going to stop telling anyone and everyone that period pain isn’t so normal after all.

McKenna Oxenden usually covers Harris County, with a focus on local government and accountability. She would love to hear your endometriosis story or answer any remaining questions you might have about the disease. You can reach her at mckenna@houstonlanding.org or @mack_oxenden on X.