Running for office is expensive, time consuming and stressful. Bryan Chu wants to do it anyway to show others they can, too.

The 57-year-old arrived in the United States as a refugee from Vietnam when he was 14. The next 30 years of his life were spent going to school, working as an engineer, then a dentist, and dreaming of a return to his homeland.

“The first 10, 20 years, Vietnam was still my country because everybody wanted to go back,” Chu said. “But after 30 years, we realized that the path to going back may be impossible. We realized this was our country now.”

Chu, president of the nonprofit Vietnamese Community of Houston and Vicinities, said he will never forget his birthplace, but he now is focused on empowering the Vietnamese-American population in Houston.

He speaks on Vietnamese radio about the importance of voting and civic engagement, has organized voter registration drives and is again considering a run for the Texas Legislature in 2026 in hopes of seeing more Vietnamese elected officials representing the community’s needs.

The Houston metropolitan area has the second largest Vietnamese population in the United States. It is the largest Asian minority in the area and has grown significantly since the beginning of the 2000s, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, giving it a significant impact on the area’s culture.

The Houston area’s Vietnamese population, however, is around half that of metropolitan Los Angeles, according to the Pew Research Center, giving the California contingent more political influence than its southeast Texas counterparts. The Southern California population also votes at higher rates and has seen far more Vietnamese Americans elected to municipal and state office. Orange County elected its first member of Congress of Vietnamese descent in 2024, a feat the Houston area has not come close to achieving.

“There’s a very limited number of elected Vietnamese officials in Houston,” Chu said.

RELATED: 50 years later, the fall of Saigon still resonates throughout Houston’s Vietnamese diaspora

The community in Houston has established its own “Little Saigon,” achieved major influence on the city’s culinary scene and is a significant part of the cultural fabric of the region. Asked what the community’s biggest remaining challenge is, Chu replied, “to become part of the government.”

Challenges with political representation include such factors as language barriers, educational attainment, economic pressures and more barriers to vote in Texas than in states like California, said Alex Thai-Vo, an assistant professor at the Vietnam Center and Sam Johnson Archive at Texas Tech.

“While legal barriers, like voter ID laws, affect all Texans to varying degrees, Vietnamese Americans often face informational, cultural and linguistic barriers that are subtler forms of disenfranchisement,” Thai-Vo said.

Vietnamese Americans are the poorest Asian minority in the city, according to a recent analysis by Rice University’s Kinder Institute Houston Population Research Center found.

Lingering effects of war

The Vietnamese War continues to be a source of trauma for residents who settled in Houston as refugees fleeing the fall of Saigon 50 years ago. Al Hoang, the first Vietnamese-American politician elected – in 2009 – to Houston City Council, faced significant backlash after taking a 2010 trip to Vietnam and later attending a reception in Houston for a visiting Vietnamese dignitary. He was ousted in 2013 by Richard Nguyen, another Vietnamese immigrant, who in turn was defeated in 2015 by Vietnamese immigrant Steve Le.

Le declined to run for reelection in 2019, and no other Vietnamese Americans have been elected to City Council since.

The lingering effects of the Vietnam War differentiates Vietnamese Americans from most other minority groups living in the country. Unlike many other immigrant groups, their arrival in the United States followed displacement and trauma rather than a search for economic opportunity, Thai-Vo said.

First-generation Vietnamese Americans tend to favor political conservatism because of strong anti-communist sentiments left over by the war, while also struggling with language barriers that make it harder to understand ballots and information on how and when to vote, Thai-Vo said.

Rep. Hubert Vo, D-Houston, was 19 when he fled Vietnam with his family in 1975. Now 68, Vo said he was fortunate to have only attended French schools in Vietnam as a child and spoke little Vietnamese. That forced him to quickly learn English because he could not rely on Vietnamese when his family moved from Lubbock to Houston in 1977.

Vo said he, like almost all of the refugees at that time, had left Vietnam with “nothing but the clothes on our backs.” However, he said he was luckier than most to be able to overcome the language barrier and become more engaged with the broader community than many other older Vietnamese immigrants.

“The first generation, because of the language barrier, they are shy to reach out to other communities,” Vo said. “When it comes to our children’s generation now, they’re not so shy.”

Younger generations of Vietnamese Americans born here or brought to the country at a young age tend to be more comfortable navigating the political system, Thai-Vo said.

“They often have different political values than their parents — sometimes leaning progressive on social issues — and may feel disconnected from ethnic community organizations that once mobilized their parents,” Thai-Vo said. “This intergenerational divide can dampen collective turnout, as there’s less of a unified political message or mobilization effort.”

Local groups, such as the Vietnamese Community of Houston and Vicinities, have a message tailored more toward the older generations that emphasizes anti-communism and are led by former refugees, like Chu.

As a whole, Vietnamese Americans had one of the lowest levels of turnout among Asian-American voters in 2020 at 55 percent, according to an analysis by the Asian American Research Center at the University of California, Berkeley.

In the Houston area, both political parties struggle to tailor messaging directly to Vietnamese voters, said Bradon Rottinghaus, a political science professor at the University of Houston. For example, he said, discussions of immigration policy focus on those from Latin America rather than Asia.

“The incorporation in your message is key to getting voters who are otherwise reluctant to vote to come and vote,” Rottinghaus said. “If that’s not done, or not done well, then it won’t work.”

Civic engagement

In Harris County, there are efforts to further engage the community and expand access to the ballot box.

The 1965 federal Voting Rights Act requires jurisdictions with significant language-minority populations provide bilingual ballots and election materials to voters. Harris County’s Language Assistance Program, based on U.S. Census findings, provides ballots and voting information in English, Spanish, Vietnamese and Chinese, according to the Harris County Clerk’s office.

The clerk’s office works with local Vietnamese organizations Viet Vote and Boat People SOS to register voters and remind residents of upcoming elections.

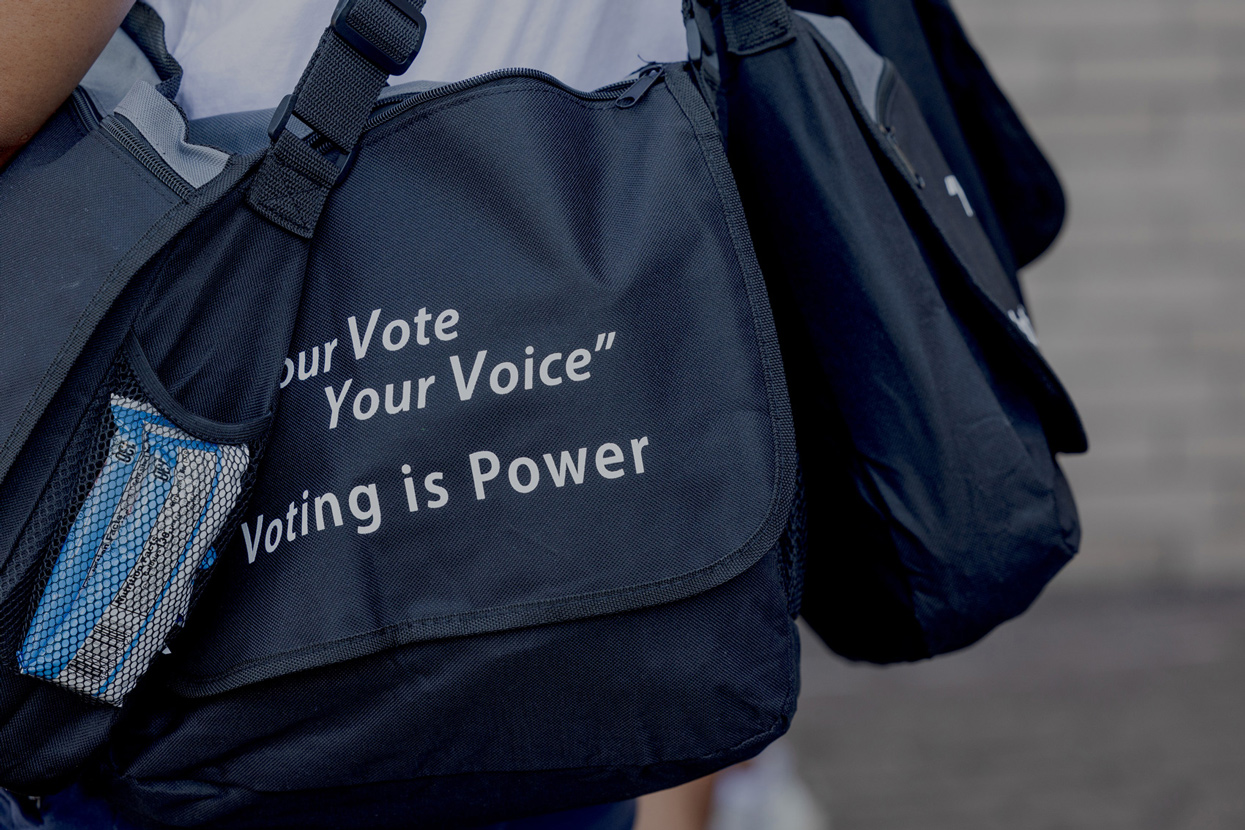

Viet Vote is a nonpartisan campaign founded in 2022 by local nonprofits Institute for Civic Education in Vietnam and Vietnamese Culture and Science Association. Viet Vote was founded because “the number of Vietnamese-American voters who went to vote in past elections has been insignificant based on election statistics, and as a result, our voice has not been heard in the mainstream as it should be,” according to its website.

Anhlan Nguyen, executive director of the Vietnamese Culture and Science Association and founder of Viet Vote, said she hopes to instill a sense of belonging and civic responsibility in the community, which, in turn, will lead to greater voter participation.

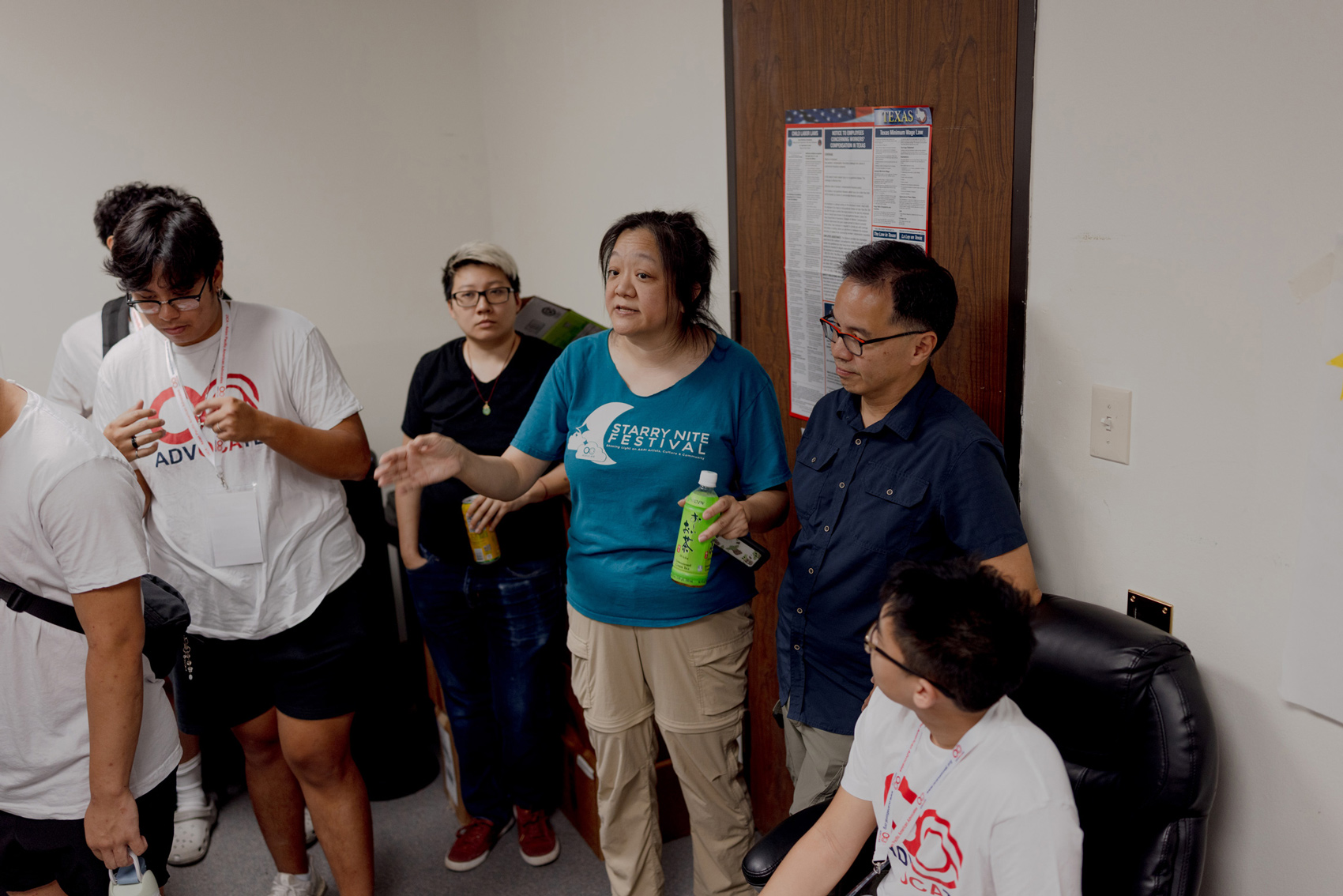

That includes a “Youth Empowerment Summit” the organization launched last year that invited 10 youth-led groups to a three-day camp that combined leadership development, community service, public outreach, wellness and mental health education, Nguyen said.

In the leadup to the 2024 election, the group also engaged in voter outreach, partnered with Harris Votes to register voters and held ballot education sessions, Nguyen said.

Nguyen said she does not fully know why the Houston community has lacked voter engagement and political candidates, but said finding the answers to those questions is why the group was formed.

“The bigger issue is, how can you instill the sense of commitment and the passion of civic engagement in younger generations up to the point we have more chances to recruit more young leaders willing to invest their time and effort into running for office? I don’t think we are there yet here in Houston,” Nguyen said.

Cecilia Nguyen, a 21-year-old Rice University cognitive science major, is a part of the younger generation working to become more civically engaged. Nguyen is the daughter of Vietnamese immigrants that lived in Saigon and emigrated to the United States in the 1990s. She was born in Houston, raised in a conservative Catholic family and has seen the generational divide firsthand.

Her father is more conservative, while she considers herself progressive on most issues. Her mother rarely votes. She sees her father’s conservatism as tied to an anti-communist and anti-China sentiment left over from the war, while she worries that her community tends to be trapped in the past by the war, leading to the occasional heated conversation about politics within her family.

“It’s become something where I can’t die on that hill,” Cecilia Nguyen said. “I have tried to in the past, and it’s often a really difficult balance to manage my relationship with my family and my views, and I’m not going to let those two destroy each other.”

As a freshman at Rice, Cecilia Nguyen interned at the Houston Asian American Archive, an experience that got her interested in civic engagement. Nguyen was aware of voting barriers in Houston that most significantly impact older generations of Vietnamese Americans that have learned little to no English. The language barrier pushes those residents to primarily engage only with Vietnamese news sources and leaves them uninformed about American politics and voting, she said.

“There’s like that whole part that’s Bellaire and Little Saigon that has a lot of elderly people that never learned to speak English or don’t speak English well and they naturally are very siloed in,” she said.

Beginning in 2023, Cecilia Nguyen started working as a poll clerk with the Harris County Clerk’s office. She sought the job primarily for the $17 an hour it offers, but also because of her ability to speak both Vietnamese and English and assist bilingual voters.

“Vietnamese people tend to open up more to Vietnamese faces who speak Vietnamese,” she said.

The efforts of Harris County leaders to push people to vote are important, but the work to fill information holes created by language barriers, like the civic engagement efforts by Viet Vote, are most important to create lasting change, she said.